Could ‘smart’ building facades heat and cool buildings?

February 13, 2024

February 13, 2024

A promising research project looks at the possibilities for thermoelectric systems to thermally condition buildings

What if we could design buildings that could heat and cool themselves? What if we do this by repurposing existing technology? And what if we could seamlessly integrate this technology into a building’s walls?

The building industry has made great progress in reducing its operational carbon. But humans still consume a huge amount of global energy cooling and heating our buildings. We need new ways to get to net zero.

As a doctorate student at University of Massachusetts Amherst, I was part of an ongoing research effort looking into the potential uses for thermoelectric (TE) materials in buildings. Several departments contributed to the project. Ajla Aksamija and Zlatan Aksamija, professors at UMass Amherst at the project’s onset, invented this patent-pending technology.

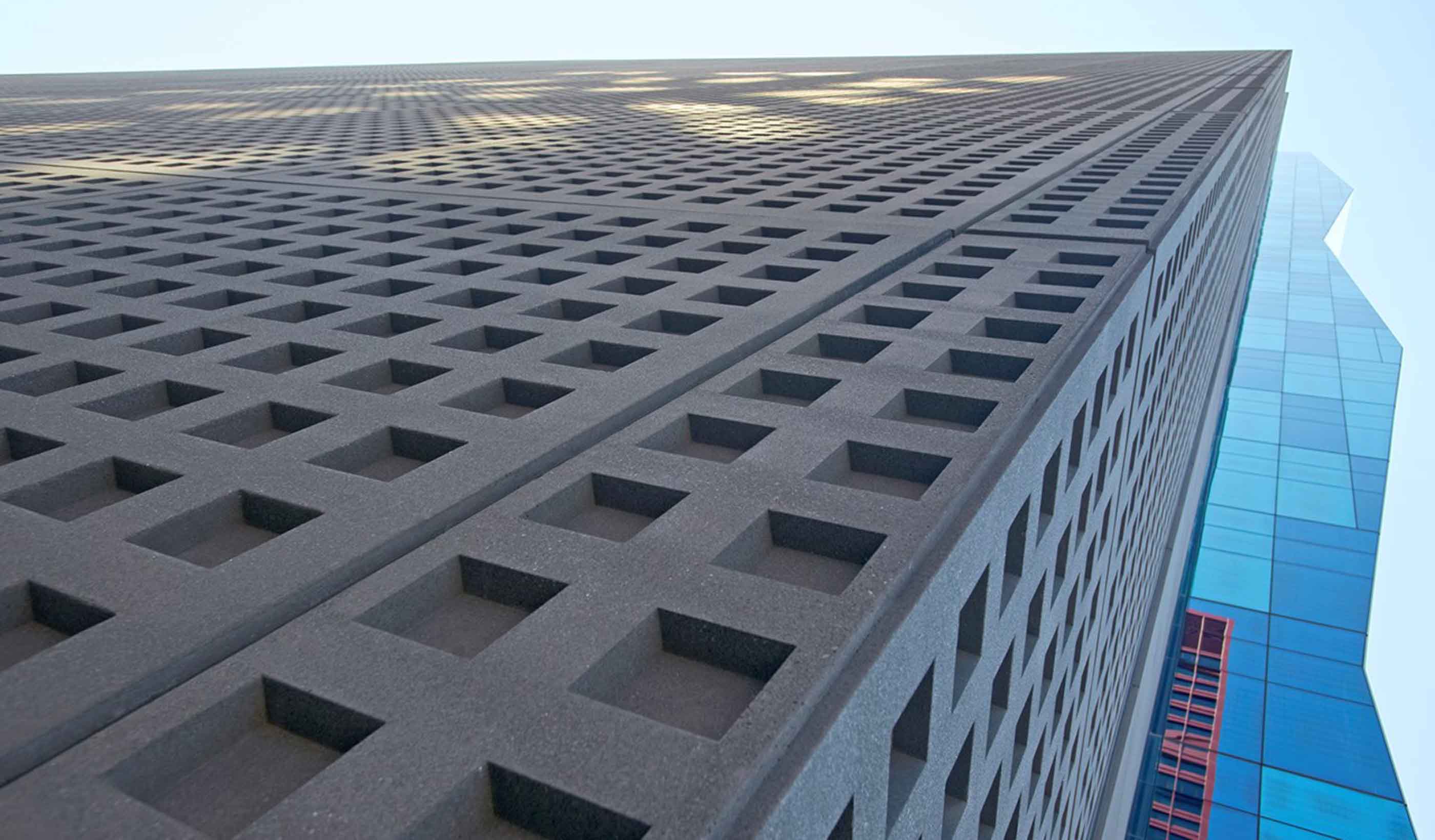

Roosevelt University in Chicago, Illinois.

Thermoelectric materials are “smart” materials. TEs can convert temperature differences (or heat flux) into electrical energy. The behavior of TE materials has been known for years, but researchers have mostly focused on new classes of TE modules (TEMs). Or they have experimented with applications such as thermoelectric generators to make cars more efficient. There has been little research on their use in the building industry.

Could we implement TE devices in building facades to use the temperature difference between inside and outside to generate electrical energy? We attempted to answer that question in our research. If we could, we hypothesized that we could use that electricity to heat and cool perimeter spaces in buildings without relying on a conventional HVAC (heating, ventilation, air conditioning) system. And we could even generate electricity when the spaces are not occupied.

Potentially, we could retrofit existing buildings by integrating TEMs in their facades. And, once available, the industry could use these systems in new construction.

By applying TE technology in buildings, we could potentially cut their carbon appetites and energy bills.

But that’s not all. Thermoelectric facades are modular. They don’t need to be connected to a conventional HVAC system, fuel source, or air ducts. They use radiant heating and cooling. TEMs are compact, reliable, and stable. They do not contain any moving parts, which reduces maintenance costs compared with conventional HVACs. These systems can store energy locally, operate quietly, and eliminate the need for refrigerants.

Potentially, we could retrofit existing buildings by integrating TEMs in their facades. And, once available, the industry could use these systems in new construction, potentially meeting most of the heating and cooling needs of the perimeter spaces in commercial buildings. In both cases, we would reduce buildings’ energy appetite from the grid. But first we needed to find out if the technology worked.

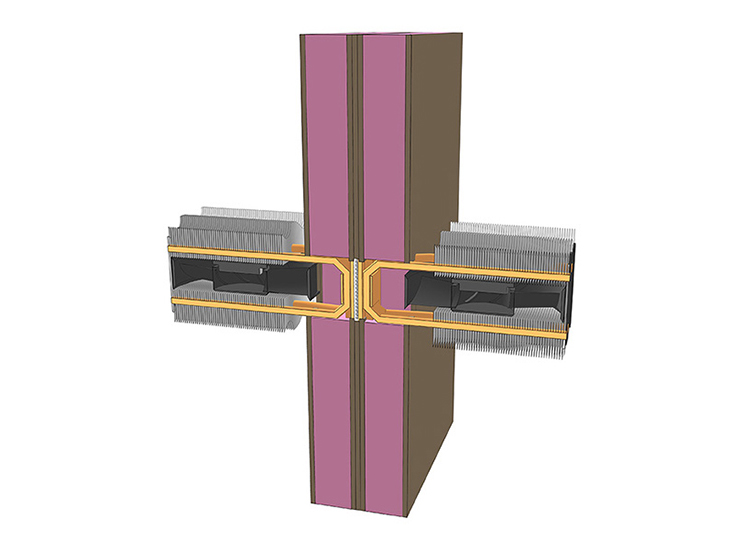

A prototype facade with TEM at center and heat sinks on either side.

The team researched TEMs integrated into facades to see if theory could be reality. In the initial phase, we built simple prototypes to test our hypothesis of TE’s heating and cooling ability. Preliminary results were promising, indicating potential.

In the next phase, we studied the integration of TEMs as stand-alone elements in the facade and combined with heat sinks in facade assemblies. We used a thermal chamber to simulate various exterior environmental conditions from 0° to 90°F. And we measured the temperature of the internal heat sinks both in heating and cooling modes. Our results showed that facades with integrated TEMs and heat sinks should operate well in heating and cooling modes under varying exterior environmental conditions.

For the next phase, the team created energy models based on our initial findings. We tested a single office space with a TEM facade and a large commercial building with a perimeter TEM facade. We compared performance with a conventional system in various climate zones and weather systems. Once again, the results exceeded our expectations. Our models showed the facade panels worked best when the temperature difference was high, as this is when they delivered more energy.

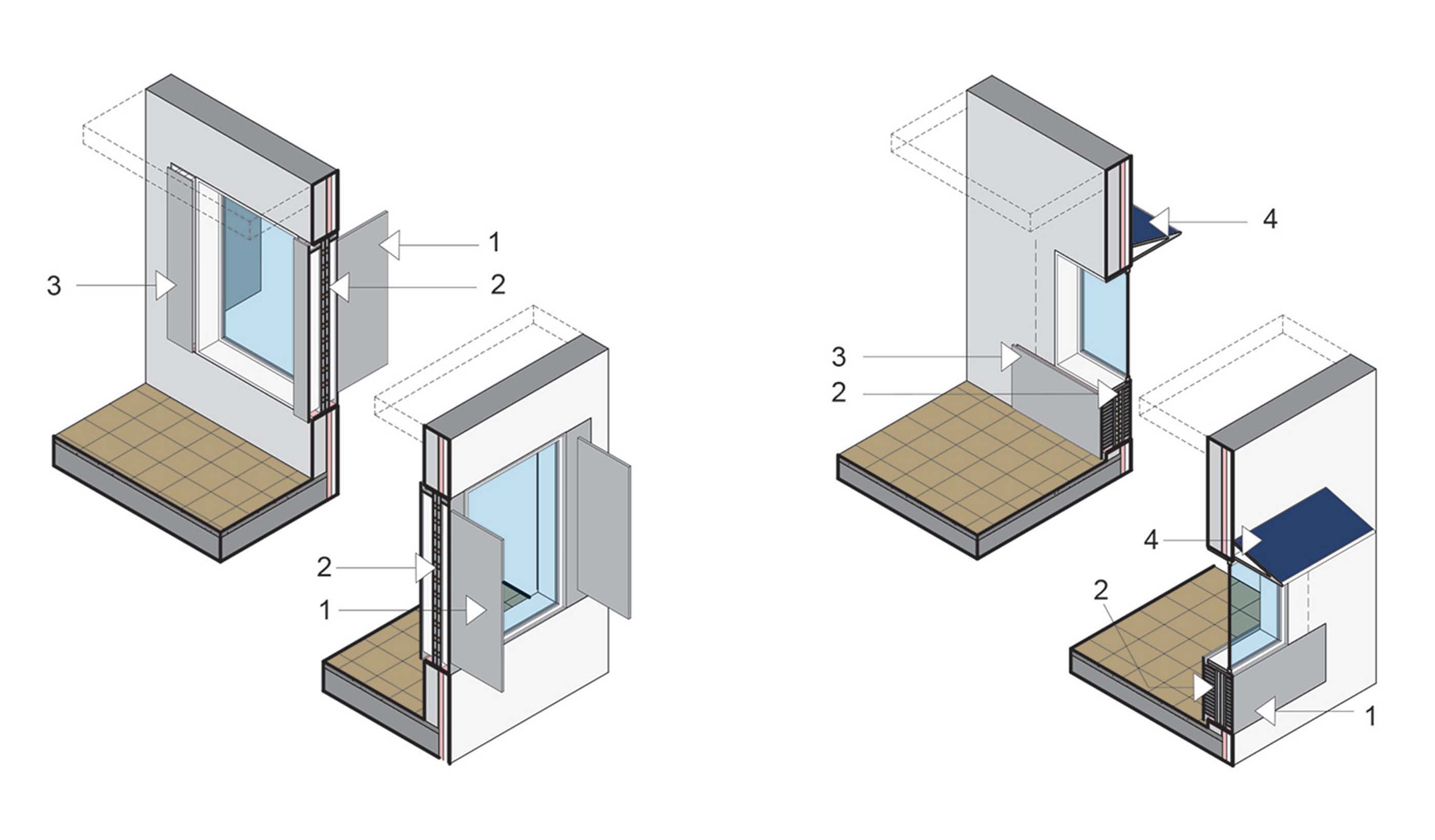

We began to look at optimizing the system. Computational fluid dynamics helped us determine that about 15 percent of the facade should be devoted to TEMs for optimal performance. Next the team designed various facade assemblies with appropriate architectural details. To gain acceptance in the industry these smart facades will need to be available with a variety of materials and styles, with window options. The team also incorporated shading and photovoltaic panels in the facade systems. There’s no reason that a facade that heats and cools can’t look good, too.

Opaque facade with window and vertical shading (left) and with horizontal shading (right). The elements include: (1) exterior heat sink, (2) interior radiant panel, (3) TEM components, and (4) photovoltaic panel.

Researchers built two full-scale working prototypes. But they have yet to test them under real-world conditions. We published various articles and research papers on our project, examples include: “Novel Active Facade Systems and Their Energy Performance in Commercial Buildings” and “Thermoelectric Materials in Exterior Walls: Experimental Study on Using Smart Facades for Heating and Cooling in High-Performance Buildings.”

The team’s research indicates that this technology has great potential. So, what's next for facades with integrated TEMs? The inventors are pursuing a patent and seeking manufacturing partners to bring these products to the marketplace. They are excited about the possibility of smart facades in the next generation of low-carbon buildings. And I’m excited to see where it goes.