New York City’s Local Law 97 is fighting climate change, focusing on sustainable buildings

March 24, 2023

March 24, 2023

The most progressive climate change legislation for buildings in any city worldwide is Local Law 97. The clock is ticking to make updates.

Home to more than 1 million buildings, New York City lives up to its “concrete jungle” nickname. Buildings of all shapes and sizes dot the compact landscape, with some of the oldest buildings dating back to 1764—and the newest rising as you read this.

On average, most of these buildings are nearing 60 to 70 years in age and require constant upkeep, with many lacking the energy efficiencies of modern buildings. As a result, the city’s buildings are also a major contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—71 percent of the city’s total emissions in 2017, per pre-pandemic data available.

But the city is taking a stand. It passed what is being heralded as the most ambitious climate legislation for buildings enacted by any city in the world. The goal? To reduce 40 percent of GHG emissions from buildings by 2030, relative to 2005, and 80 percent by 2050.

By 2030, just seven years from now. Did you catch that? Yes, that’s a short timeline! Is it doable? Absolutely! Let’s dive in.

On average, most of these buildings are nearing 60 to 70 years in age and require constant upkeep, with many lacking the energy efficiencies of modern buildings.

The New York City Building Emissions Law, or Local Law 97, sets annual emission caps on buildings greater than 25,000 square feet. That’s about 50,000 buildings, or nearly 60 percent of the city’s building area. 59 percent is residential and 41 percent commercial. Emission caps are calculated for each building by multiplying its square footage by its emissions intensity limit (metric tons of CO2e per square foot).

The legislation sets limits beginning in 2024 for the most carbon-intensive 20 percent of buildings to target a 40 percent reduction in GHG emissions by 2029. In 2030, this expands to target the most carbon-intensive 75 percent of buildings to reach goals by 2034.

New York City government buildings face even stricter guidelines, with a 40 percent reduction in emissions mandated by 2025 and 50 percent by 2030. Exceptions are made for religious buildings and rent-regulated and low-income housing units, though those buildings are still required to adopt prescriptive energy-saving measures.

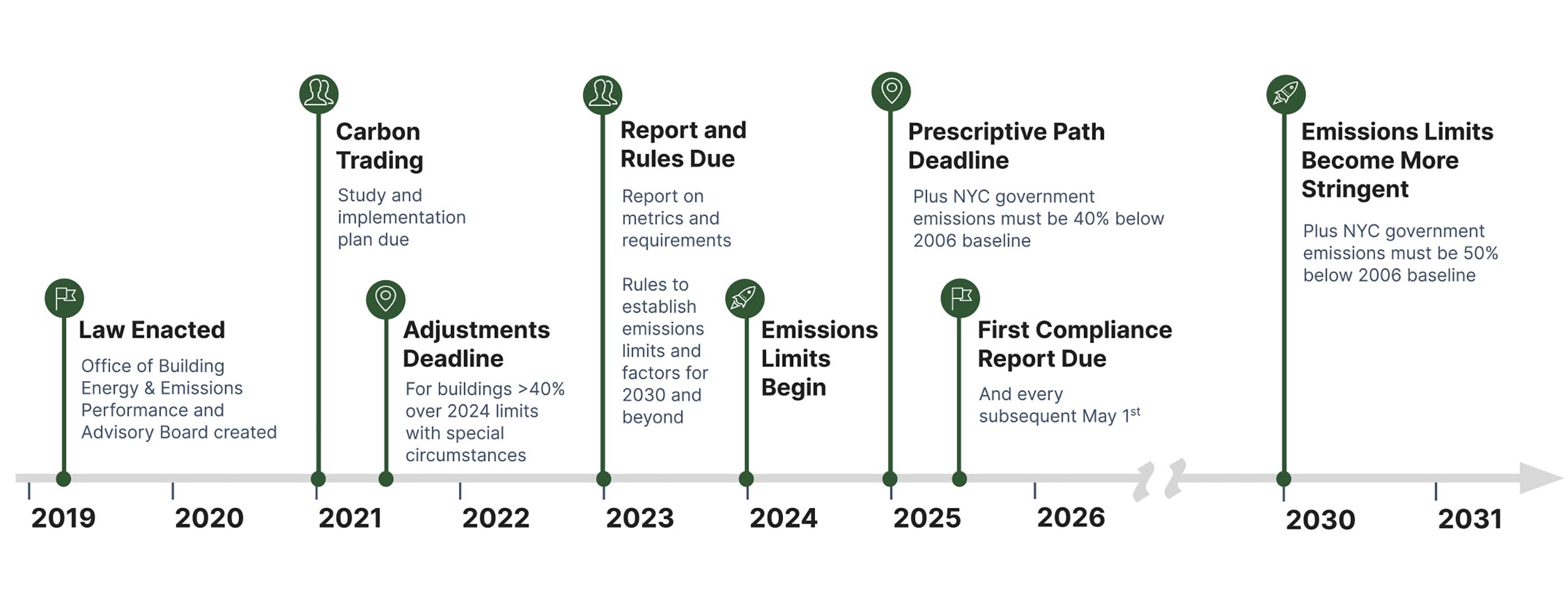

Rollout timeline for the New York City Building Emissions Law. Courtesy of Urban Green Council.

Building X is a mixed-use, 55,000-square-foot building in midtown Manhattan. Retail space on the ground floor occupies 10,000 square feet, with residential and accessory spaces occupying the remaining 45,000 square feet.

Local Law 97 sets annual GHG emissions intensity limits by occupancy classification in 2024:

So, for 2024, the GHG budget for building X is calculated as:

That gives the building a budget of 421.85 tons CO2e.

Now, here’s what we found when looking at the building’s utility bills:

With an electricity coefficient for the 2024-2029 reporting phase of 0.000288962 tCO2e /kwH, and a steam coefficient of 0.00006640 tC02e/kbtu, we can run the following calculation to get the building’s 2024 GHG consumption:

There is also the option, under recently passed technical amendments to the legislation, to run more detailed calculations for carbon emissions from electricity based off time of use.

The result? Building X clocks in at 480.25 tons CO2e, exceeding its budget by 58.4 tons. It’s time to head back to the drawing board—or pay up! Annual penalties are $268 per tCO2e excess ($15,652 in the case of building X).

Disclaimer: The preceding example is a specific interpretation and could change depending how spaces like mechanical rooms are classified. It could also change based on further legal guidance from New York City.

New York City’s buildings are a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions—71 percent of the city’s total emissions in 2017.

Local Law 97 does offer flexibilities, like the option to purchase renewable-energy credits and receive a deduction from the reported annual building emissions of up to 100 percent. Property owners can also file for an adjustment and claim that it is not reasonably possible to make the necessary improvements, particularly if the building is constrained by landmark designations or sits in a historic district, or if there is lack of access to energy infrastructure/other space constraints.

For the 2024-2029 reporting timeframe, there are additional adjustments for buildings that exceed their emissions limit by more than 40 percent if they face excess emissions due to 24/7 operations, operations critical to human health, high-density occupancy, or industrial processes. In these cases, the building owner must submit a long-term plan to meet emissions limits for 2030-2034. It’s important to note that the deadline to submit the adjustment report has already passed (June 2021) for excess emissions and July 2021 for not-for-profit healthcare.

Here at Stantec, we’re already working with property owners and managers to advise them about Local Law 97 and help them begin planning for the years ahead.

If a building consumes less than the limits set forth for 2024-2029…great! But would it meet the 2030-2034 limits? What about limits for 2035 and beyond? Likely not. We’ll be seeing a lot of retrofitting in the next 10 years.

As a property owner, is a retrofit in your future? Start by looking at your utility bills. Run the calculations to see where you stand. Keep in mind that with different interpretations of the law, you may be over or under right now.

From there, conduct a facility assessment to see why you are where you are. Are there things you can be doing better to curb energy usage? Begin itemizing a list of tasks, prioritizing potential upgrades based off the previous Local Law 87 energy audits. And think about the things you need to begin budgeting for now.

Here at Stantec, we’re already working with property owners and managers to advise them about Local Law 97 and help them begin planning for the years ahead.